When you first meet Charles Goslin you can’t help but think: courteous Bostonian gentleman. It could be his demeanor—quick-witted, yet mindful and attentive to your words. His brown tweed jacket, button-down shirt, and English shoes help the equation. In fact, Goslin is from nearby Attleboro, Massachusetts.

In 1954 he received a BFA in graphic design from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). One instructor in particular, someone who made a difference for him, was James Pfeufer (1950–1960). “Jim critiqued design projects with the utmost respect. He taught me how to value graphic design.” RISD gave Goslin the craft and inspiration to apply to the top design offices of the day.

Upon graduation, Goslin began working for noted American designer Lester Beall. “The minute I walked into Beall’s studio at Dumbarton Farm, as Beall called it, I knew it was the place for me,” Goslin recalls. “The studio wasn’t decorated with utilitarian color charts or production materials; only framed photographs and paintings, carefully hung alongside choice design projects pinned to the walls…the message was that design not only solved the client’s problems, it also nourished the designer creating the work and the audience viewing the work.”

After four years of what Goslin fondly calls “an apprenticeship,” he was ready to try his hand at his own studio. “I wanted to work on my own because I didn’t want to compromise with anybody.” In 1958, Goslin transplanted himself to brash and tough Brooklyn. What would have seemed to be a mismatched environment, was in fact, a beautiful fit.

Victorian architecture and leaded Tiffany windows helped. They connected him with a genteel, turn-of-the-century, urban landscape. Slick glass and steel weren’t quite Goslin’s aesthetic. A live-and-work brownstone is where he settled and where he continues to work today.

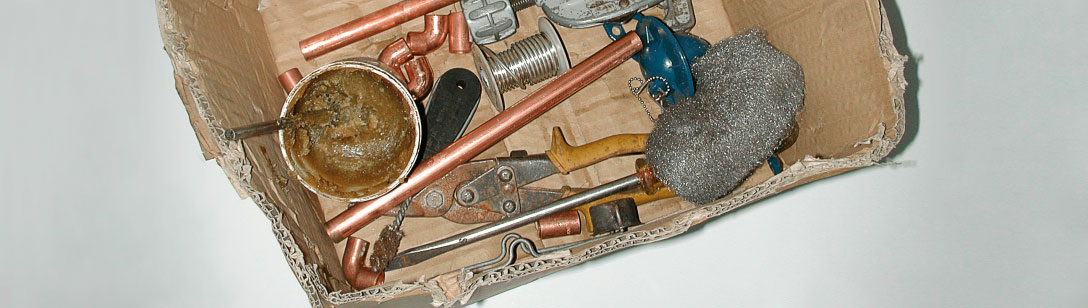

Clients include non-profit organizations, local businesses, and large corporations. But regardless of the budget, each project receives an equal amount of attention from Goslin, revealing a genuine love of the image-making process. In a presentation given to the New York Chapter of the American Institute of the Graphic Arts (AIGA) in October 2000, he playfully likened himself to a simple shoe cobbler—as close as possible to his work. “To get down into it, to push things around with my hands, crafting a design; that’s what I like best.”

Goslin has also been pushing and prodding students for over 37 years. A dedicated teacher of graphic design and illustration, both at Pratt Institute since 1966 and at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) from 1974—1985, he has inspired literally thousands of designers. His favorite projects are handing out news clippings based on strange but real stories. There’s one from the New York Times about an automotive product called “Nuance” which gives interiors that “new car smell:” Design an advertisement for this pump spray invention. Or the article in the Daily News about an animal chiropractor—what would the brochure’s cover for this odd practice look like? The student’s job is to sketch, conceptualize and interpret, but above all, the student must communicate.

Over the years, Goslin has seen the design and education world move from Modernism’s Swiss International Style of the ’60s, on through to the computer age and Postmodern eclecticism. But Goslin never wavered from his particular method of communicating. “I never bought into the ‘less is more’ Helvetica approach. But then again, I was never really into fashion.” Ironically, Goslin has a Swiss heritage and jokingly says “The Swiss have an amazing ability to say nothing beautifully.”

Maybe the Yankee in Goslin is what comes through. There’s a basic honesty inherent in his design. “I want to put myself in my work and not hide the fact that I’m designing it.” This basic idea extends to his teaching method. Design students are encouraged to speak through their work, and to speak with style. “Very often my students confuse technique with style. I tell them to never try to find ‘a style’ because your own individual style will find you. Style comes to you when it is ready and comes as inevitably as sweat on a July day.”

In order to speak with style, you have to begin by having something to say. To be sure, Charles Goslin has lots to say. He’s a storyteller of the first degree. ”I hate the idea of stating one thing and plopping it in the middle of the page,” says Goslin. The result is that each of his projects is like a collage. But even with the densest works, there’s a clarity nonetheless.

It’s distilled through the idea. “Visualizing ideas is the most important thing we do as graphic designers. Without an idea, you’ve said nothing. But it’s also not just expressing an idea. It’s making a graceful idea, a beautiful idea.”

For the cover of a 50th-anniversary calendar of a hardware store in Park Slope, Brooklyn, an image of the neighborhood icon is used—the arch in Grand Army Plaza. “The concept was to say that all the other hardware stores in Park Slope don’t matter,” says Goslin. “Tarzian is the hardware dealer of Park Slope.”

Within a stark black and white pallet, Goslin is able to create a rich and textured color. The effect is truly masterful. Hand-drawn sketches, abstract shapes, posterized photographs, enlarged dot screens, and jewel-like type: They all add up to strong and straightforward architecture of graphic illustration.

Goslin’s own work, and the student projects he assigns in class, might be reflective of all the newspapers he reads—true stories, in black and white. “Current history has an amazing ability to clarify the mind,” Goslin says. “Analyzing the news, or a student’s work, forces you to analyze your own work.” Actually, Goslin’s work is a bit like a typographic narrative. It’s what makes his work so intriguing. The collaged graphics all re-paraphrase the basic idea of the story until the reader understands. He never gives up trying to communicate.

It’s the same with his teaching. Goslin never seems to give up on his students. And decades worth of professional designers and illustrators never lose touch with him. They become part of a large, extended family because, for each one, Goslin somehow made a difference.

Scott W. Santoro, Worksight

January 2004

Addendum: Charles Goslin passed away on May 16th, 2007, collapsing after teaching two summer design classes at Pratt Institute. He went out the way he had hoped. This is a reposting as I have just completed the archiving of his work, which now lives at The Herb Lubalin Study Center and the Rhode Island School of Design. See more examples of his work at peoplesgdarchive.org